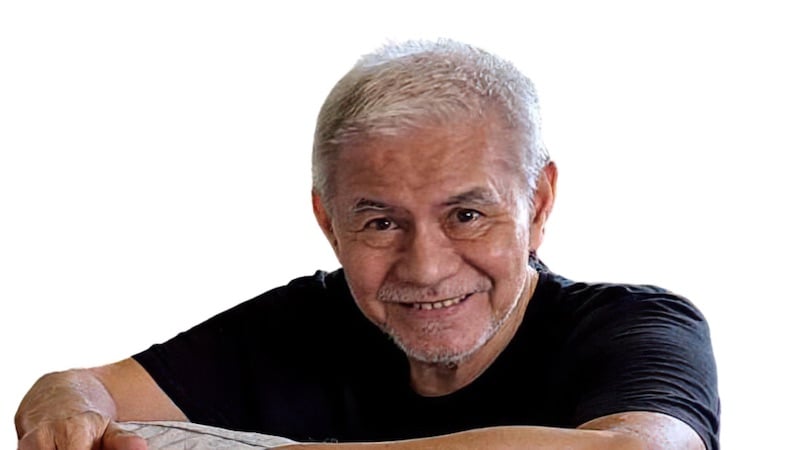

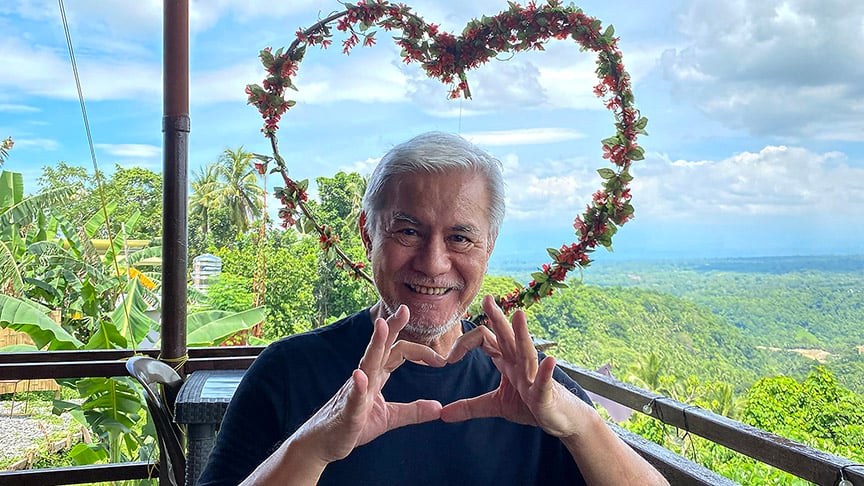

DAVAO CITY (MindaNews /17 May) – The father of health cooperatives in the country, Dr. Jose Ritzi “Ting” Manigque Tiongco, Chief Executive Officer of the Medical Mission Group Hospitals and Health Services Cooperative-Philippines (MMGHHSCP) Federation passed away at 10 p.m. Tuesday in a hospital in Taguig City, his family announced.

He would have turned 76 on June 19.

In a brief statement, the family said Tiongco passed away peacefully at the St. Luke’s Medical Center in Taguig City, surrounded by his loved ones.

“The Tiongco family honors the memory of our dear Jose ‘Ting’ M. Tiongco. Let us celebrate his life, filled with love and passion for service. We ask for prayers for the eternal repose of his soul,” the family said.

The wake will be in Manila and Davao – at the Chapel 1 of The Heritage Park in Taguig City from May 18 to 19 and the Waling-Waling at the Cosmopolitan Funeral Homes along Cabaguio Avenue in Davao City from May 20 to 22. Interment will be on May 23 at the Davao Memorial Park after the 7:30 a.m. funeral mass at the Carmelite Monastery.

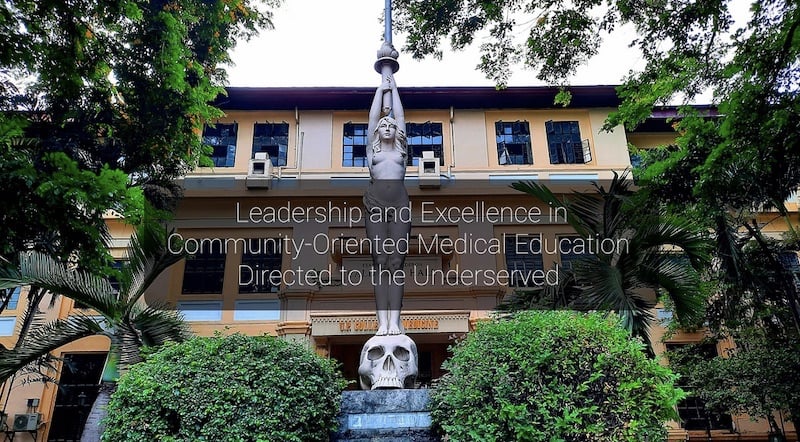

Born in Davao City to Boholano settlers Gaudioso Tiongco and Caridad Manigque, he finished Elementary and High School at the Ateneo de Davao, Pre-Medicine at the Ateneo de Manila and Medicine at the University of the Philippines College of Medicine (UPCM), Class of 1971.

He trained at the UP-Philippine General Hospital (UP-PGH) Department of Surgery until 1976, returned to Davao City as volunteer consultant at the Davao Medical Center (DMC; now Southern Philippines Medical Center) and left for Vienna, Austria in 1979 for neurosurgical training at the Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien. On his return in 1981, he chaired the Department of Surgery in DMC, where he developed a training program for young doctors, emphasizing on what he had repeatedly pushed for and fought for while a student at UPCM and doing internship and residency at the PGH: that Health is a Basic Human Right.

The long journey that eventually led him to what is now a nationwide network of health cooperatives providing “adequate, affordable, accessible, and appropriate health care to the marginalized” began when he was a student at the UPCM half a century ago.

Asked by a young fraternity brother to describe his med school days, Tiongco replied: “I was a renegade. Still am.”

Tiongco was often described as a renegade, a maverick, a rebel with a cause, a sociopath, a trailblazer, a crazy dreamer, a visionary. Authorities in UPCM, PGH and DMC looked at him as a “troublemaker” for questioning and challenging them on policies and holding them accountable for every centavo of taxpayers’ money. Fellow doctors, other health professionals and patients as well as the public rallied behind his cause in protest actions at the UP-PGH in the 1970s and the DMC in the 1980s.

As editor in chief of UP Medics, the medical school’s newsletter, “he did not just report the news, he made news,” wrote Abdelsimar Tan Omar II for Phi Kappa Mu’s “Brod Feature.”

Tiongco recalled in his 1996 book, “Child of the Sun Returning,” that as editor, he wrote about “the oceans that existed between the Preaching of Medicine in the UPCM and the Practice of Medicine in the PGH.”

“They taught us Hygiene and Community Garbage Disposal in the air-conditioned

classrooms of the UPCM. A few meters away in the old PGH, they threw rotting placentas and surgical specimen in a stinking garbage pile under the water tank. Inside PGH, overworked resident doctors and interns fought a valiant losing battle against the effects of filth, infection, malnutrition, parasitism and corruption,” Tiongco wrote.

He called for a dialogue, published its proceedings and wrote stinging editorials that disturbed those who should be disturbed.

In Omar’s account, when Tiongco found out that the PGH budget was still controlled by Congress even as PGH had been turned over to UP a decade earlier, he sought an audience with UP President Salvador Lopez for UP to assume full responsibility over PGH, to handle the PGH budget instead of Congress, and for PGH directors to be appointed according to academic requirements set by UP and not according to the whims of politicians.

Six months and still no action later, Tiongco “led preparations for a hospital strike in PGH, the first ever in the world,” Omar wrote.

“Due much to his efforts,” students from UP Diliman and UPCM, PGH nurses and employees, patients and their relatives, marched from Diliman to PGH, eventually forcing Congress to pass a bill handing over the PGH budget to UP.

Tiongco did not spare the UPCM. He criticized how an institution funded by taxpayers was training doctors who were to become an “embarrassing luxury few of our countrymen could afford.”

On his last year as a surgical resident, Tiongco, then president of the PGH Physicians’ Association, lobbied to allow limited and supervised private practice for the more senior residents “to provide some financial support for their families after their salaries ceased.”

According to Omar, Tiongco proposed this as an incentive for the doctors to remain in the country and not leave for abroad like majority of UPCM graduates. The PGH director said his proposal was immoral, to which Tiongco replied that there was “nothing more abusive and immoral in the PGH than the fact that the majority of the residents trained and honed their skills on poor Filipino patients but used them to advantage on rich American patients later.”

“Throughout his life, Brod Ting dissented when the need arose, moved in the face of apathy, paved the way for the realization of many of his strong-held convictions and as he puts it, ‘raised hell’ all along the way,” Omar wrote.

Die, if not physically, then certainly professionally

Tiongco never dreamt of going abroad to practice Medicine. At the end of his training in 1976, he declined PGH’s offer for a consultancy in surgery, to come home to Mindanao.

“Dr. Porfirio Recio, then chairman of the department, predicted I would probably die, if not physically then certainly professionally, in the provinces. He predicted that in a couple of years, if I survived in Mindanao, my surgical practice would be reduced to doing thyroidectomies and hemorrhoidectomies,” Tiongco said in a lecture in PGH in 2014.

Tiongco did more than just thyroidectomies and hemorrhoidectomies. He became a much sought after surgeon, trained at least 49 young doctors in Davao City and neighboring areas in Mindanao to become surgeons, and became the father of health cooperatives.

But he had to give up his knife at age 45 to spread the word about health cooperatives and help doctors of like mind and heart across the country to go the health cooperative way, to put “health in the hands of the people,” to ensure health care is accessible and affordable to all, a movement that Health Secretary Juan Flavier described in 1992 as “the wave of the future.”

Food, clean water, adequate shelter

It was at the PGH where Tiongco saw “too many patients with precious little to work with” as equipment were almost always out of order or had no parts or reagents, supplies were always short “and medications, rare as hen’s teeth.”

“On top of all that was the terrible realization that medical school provided only a modicum of the vast amount of knowledge one had to have to be able to do creditable surgery,” he wrote.

At PGH, he realized that many of their patients “died of the preventable social disease called Poverty too often that people became inured.”

“I came to know Death by so many faces and so many names; some of which, I would carry around with me for a long time. They would dance around my head deep into the night in a dizzying whirl of IFs and BUTs. There was really nothing a doctor and a surgeon could do about it. It was not part of our education and training.”

Addressing the issue of poverty would be part of his surgical training program in Davao City.

In a July 2013 open letter to the UP College of Public Health where he and 17 other heads of MMG chapters across the country enrolled for a Master of Hospital Administration degree, Tiongco said government pays lip service to the fact that “communities may look at health, or the lack of it, in another way, as a social event or community concern, as it should be.”

“But they blithely continue to pursue the present dominant world order’s thrust towards a centralized health care delivery system that views illness as a personal event and the hospital and its related facilities as the main foci in health care delivery. They ignore the community’s needs in basic health care such as enough food, clean water, and adequate shelter.”

He said the Department of Health “seems to have nothing to do with these three basic needs. Neither, it seems, do the University of the Philippines College of Medicine and other related branches of Health education” in UP.

Earlier, at the 11th Post-Graduate Seminar for Emergency Medicine at the UP-PGH on November 17, 2011, Tiongco said: “We in the UP-PGH and all the other training hospitals in the country were trained to deliver health care along western lines. Western medicine focuses on the disease, the tissue, the cell, the chromosome, the DNA, the molecule, the ion. Our people apparently want us, as doctors and guardians of the health of the community, to look at health in another way. Health is about people. Health is about families and communities. Whereas the present dominant world order looks at disease as a personal event with financial considerations, the Filipino looks at disease as a social event with cosmic considerations.”

He found it unacceptable that 68% of the population in the Philippines die without seeing a doctor or a nurse.

“Today, in spite of the supposed progress after martial law, we discover to our chagrin that 68 out of 100 Filipinos die without seeing a doctor or a nurse! What has our country been doing about this? What has PGH been doing about this? What have we, as doctors, been doing about this? What have you personally been doing about this? Or are you going to tell me that as a doctor, this is not your concern?,” Tiongco asked his audience.

He recalled that after leaving UP-PGH in 1976, he would often look back “in anger at what UP-PGH has done or more importantly has not done to the least of our brethren here in the Philippines.”

“Serving the poorest of the poor”

On his 70th birthday on June 19, 2017, in a party tendered by the MMG Federation, his elder brother Gari, a lawyer, shared how PGH transformed his doctor-brother. “Ten years of interacting with the masa, the men in the streets, the poorest of the poor, completely changed his persona. From being an elitist, due to his upbringing and his environment in school, he came down from his ivory tower and identified himself with the working class, the masa.”

“I saw him cringe in pain as he told me the story of a mother of a sick malnourished child who had to skip her meals to buy basic medicine for her child. He witnessed how these people endured sufferings beyond the limits of sacrifices. As time went on, he saw more deprivations, more sufferings, more unnecessary deaths and many a time, Ting had to shelve out his meager allowance to buy the medicine to save an unknown patient. He cried with the family whenever unnecessary death occurred and the patient would have been saved for a few hundred pesos of medicine. He seemed to have lived with them in wanton deprivation. By the time of his mid residency in surgery, he sold his soul not to the devil but to the nobility of serving the poorest of the poor, the hoi polloi, men in the streets. He was an angry young man questioning the inequities of the society. In all honesty, his passion sent quivers to my spine but thank goodness taking arms was not part of his passion,” said Gari, who passed away in August 2020.

Awards, Books

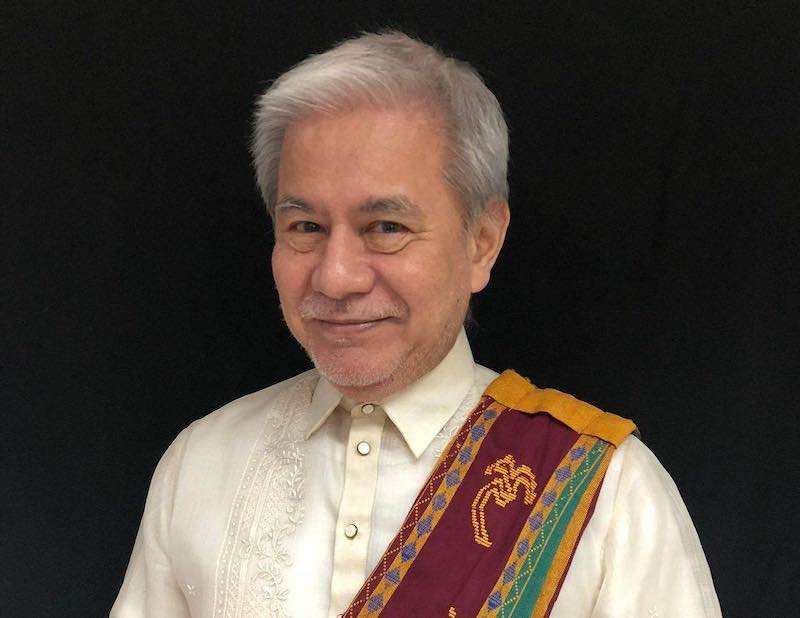

In 2007, Tiongco was conferred the Ozanam Award by the Ateneo de Manila University where he finished pre-Medicine. “The patriotic and radical approach of your cooperative health system is anchored on the justice of giving the poor the Health and Humanity they deserve,” the Ateneo said.

In 2008, the Ateneo de Davao University where he had his primary and secondary education, conferred on him the Dr. Jess and Trining dela Paz Award “in recognition of his advocacy and work in providing affordable and accessible health care to the poor and the general population through the Medical Mission Group Hospitals and more than fifty hospital cooperatives throughout the country.”

He was nominated for prestigious local, national and awards that required the signature of nominees. He did not sign them.

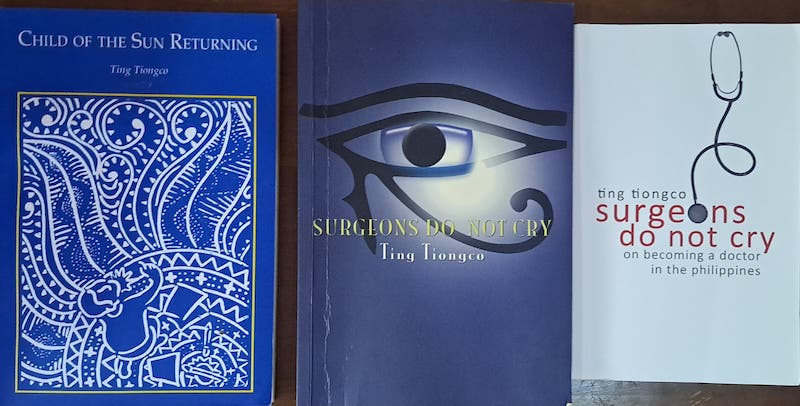

He wrote two books — “Child of the Sun Returning,” and “Surgeons Do Not Cry” – the first published in 1996 on the birthing of the first health cooperative in the country, the second on his “ten-year development as a doctor and a surgeon at the UP-PGH.”

In both, he preferred to use “Ting Tiongco” as author.

The stories in “Surgeons,” about everyday life as a medical student, intern and resident at the UP-PGH, were originally written for “Child of the Sun,” his column in MindaNews, and compiled into a book published by the University of the Philippines Press in 2008. The book has become a required reading for medical students in a number of universities and has had at least five printings, including a student edition.

In her review of “Child of the Sun Returning,” Ceres Doyo of the Philippine Daily Inquirer (PDI) described it as “a first person account, a meditation, a medication (for floundering souls), a manifesto, a treatise, an autobiography, a desiderata.” The book had its second printing in 2018.

Last month, Tiongco vowed to resume writing his MindaNews column, “Child of the Sun,” and compile the pieces later into a third book whose focus would be on the management of health cooperatives. He also spoke of putting together another book on the histories and experiences of the MMG chapter-members, for their 25th anniversary as a Federation this year.

Not as good but better

While the first cooperative hospital was inaugurated here in 1991, the concept of a health cooperative had its beginnings in 1981 at the DMC when the 34-year old surgeon, fresh from Vienna, launched the training, the first ever in DMC and the first in Mindanao.

The training came right smack into a raging war in Mindanao. Davao City was then developing into what the military would later refer to as the country’s “Killing Fields” and “laboratory for urban guerilla warfare” of the New People’s Army. Killings were perpetrated by state forces and the NPA’s “Sparrow” units. Elsewhere in Mindanao, government troops clashed with Moro or communist rebels and civilians were caught in the crossfire. Surgeons were badly needed.

What PGH was to Luzon, DMC was to Mindanao. “The hospital of the people with no other choices. The hospital of the sickest of the sick among the poorest of the poor,” was how Tiongco described it.

“I was not training the young doctors to be as good as I was. I was training them to be better,” he declared.

Part of being “better” was to design the training program differently from PGH. “I did not want to train the resident doctors the way I was trained in PGH. There, we went through the gristly mill where the daily grind focused on the What, When, Where, Who and How of illness. One necessary question was unasked: WHY,” he wrote in 1996.

And there were so many whys, among them why the people “could not afford the treatment prescribed in our textbooks and taught to us in Medical School,” why were there no equipment, supplies and medications that they badly needed in the operating rooms, the Intensive Care Unit and the wards.

The young doctors had to be ready to answer and offer solutions to the many “whys.”

Among his trainees was Dr. Leopoldo Vega, who would later head the DMC/SPMC and was named Health Undersecretary under the Duterte administration.

Tiongco also did a similar training at the state-run Davao Regional Hospital in Tagum, Davao del Norte.

“Multiply my mind and my hands”

The trainings were not just for the love of surgery but for self preservation as well. “There was a war going on in Mindanao. There was a frenzy of patients in the wards and emergency rooms. I was wearing myself out to a frazzle in the operating rooms. It was necessary to multiply my mind and my hands as soon as possible to save my health,” he said.

“I did not know then how to multiply my heart. It remained in a conundrum of contradictions,” Tiongco wrote in “Child of the Sun Returning.”

In his trainings, he told the young doctors not to accept the “lame song-and-dance routine of ‘no drugs, no records, no equipment, no reagents, no supplies or no manpower’ as excuses for the death of any patient in the surgical wards.”

“Residents were instructed to beg, steal, borrow, plunder, pillage, and rob whatever was needed by our patients to survive. No patient died in the Department of Surgery unless the doctor died first.”

But after training them, Tiongco’s problem was where would they go to practice their specialty? The district hospitals in the countryside were not equipped for surgery while the private hospitals in the cities were “dominated by doctors who were jealously guarding their turf and would not allow the graduates to practice surgery in the city.”

Tiongco was worried that they would have “no support for their families, nothing to do, and nowhere to go. Except perhaps to USA. But part of my training was for them not to do that.”

The DMC was not just catering to patients within the city but from other regions in Mindanao. But the middle class who could no longer afford private hospitals because of the economic crisis, crowded into the wards of DMC and “displaced the lowly, the poverty stricken, and the silent and docile uneducated from their sick beds and from the paltry services that the government hospital had to offer.”

“Guerrilla hospital”

Tiongco and his trainees – “crazy dreamers” as they were referred to – gathered for “dreamking” (dreaming and drinking) sessions to discuss proposed solutions.

They would later form the core of what would be the Medical Mission Group Foundation and later the first health cooperative in the country bearing the same name.

While still a foundation in the 1980s, the “dreamking” surgeons set up what they dubbed as a “guerrilla hospital,” using equipment borrowed from a hospital owned by the family of a doctor, to do ambulatory surgery on middle class patients from the DMC to decongest it for the sake of the poorest of the poor. They also opened a similar hospital in Tagum, Davao del Norte.

Tiongco said they were hitting three birds with one stone: provide private practice for the young surgical specialists who graduate from the training programs; provide fast, expert, and affordable surgical services to the marginalized middle class patients who could no longer afford the high fees charged by private hospitals; and decongest the surgical wards in the government hospital to ensure that the truly indigent would be served.

The government accused them of “stealing” patients. They were unfazed.

Cooperatives

The shift to cooperative was brought by a confluence of events. A government mandated across-the-board wage increase put the foundation in a bind. It could not afford the increase and was forced to consider retrenchment of some employees. While this was happening, an allied group in the resistance movement against Marcos which had unpaid debts in the hospital, came in to organize a labor union but lost in the certification election.

The “crazy dreamers” offered to sell the hospitals to the workers in exchange for around 200 pesos each from them. They did not know much about cooperatives then but liked the one-person, one-vote policy and after attending seminars, the cooperative of doctors and other health professionals, and their hospital workers, was born: the Medical Mission Group Hospital and Health Services Cooperative (MMGHHSC) that would, in 1991, run the country’s first cooperative hospital and cooperative health fund.

Yet another significant event was the meeting of Tiongco and lawyer Josefito Guillermo, then the manager of the Cooperative Bank of Davao City (CBDC). Like Tiongco, Guillermo was also a “dreamker.”

The banker asked the surgeon if their cooperative needed a loan.

Commercial banks had turned them down but this small cooperative bank whose daily deposits came mostly from market vendors and farmers, was willing to finance their dream hospital, a hospital that would be owned by health professionals and hospital workers, including janitors. The prospects of a cooperative health fund that would ensure the poor could access health care also got Guillermo interested.

Tiongco would soon become a member of the CBDC board and later its chair. He and Guillermo would blaze the trail for an energized cooperative movement in the city that embraced all sectors – from vendors to doctors.

It was the heyday of cooperativism in the city. Inspired by the health cooperative, other sectors, among them pilots, media, engineers, artists also set up their own.

“With the entry of professionals led by the doctors into the CBDC, the bank was now able to balance the seasonal financial activities of the farmers with the daily and more predictable financial activities of the professionals and their service cooperatives” and the stability of that configuration boosted the bank’s assets to 200 million pesos in five years, Tiongco wrote in 1996.

The first cooperative hospital was inaugurated in Davao City on November 16, 1991, a week after the health cooperative was featured (“The doctors who refused to say die”) in the PDI’s Sunday Inquirer magazine. Soon after, doctors of like mind and heart across the country, flocked to the city to learn how they could replicate it in their areas.

Surgery or Health Cooperative

Tiongco and his group got invited to different parts of the country, and later abroad, to talk about health cooperatives.

In 1992, the newly-appointed popular Health Secretary, Flavier, visited the cooperative hospital and hailed the cooperative health system as “the wave of the future.” Former President Corazon Aquino also came to visit and so did senators and congressional representatives.

The Department of Health under Flavier included cooperative health care on its top 23 priority tasks in 1993 (23 in 93).

As more invitations came, Tiongco had to choose between Surgery and the Health Cooperative.

“At 45 years of age, I was at the peak of my career. I was totally in love with Surgery. My life was my knife. My knife was my wife. I could not imagine myself without Surgery.”

He gave up his knife to go full time in the health cooperative.

“Here with the health cooperative were at last the answers to the questions we were asking. Here was a chance to help heal the welter of wounds the body and soul are heir to. Here at last was the chance to be the doctor I had longed to be – a healer in all his humanity,” he wrote.

Traveling around to preach the gospel of health cooperativism was “hard work, often more difficult than surgery. But it had become a mission for me. Sometimes, when dog-tired and disappointed, I would get the feeling that somehow, I was merely following orders. I was being used for a higher purpose. I had become an instrument. I had become my knife.”

Tiongco was invited by the United Nations-World Health Organization (UN-WHO) to be a keynote speaker during the 20th anniversary of the Alma-Ata Declaration in Almaty, Kazakhstan in November 1998. The 1978 declaration recognized primary health care as a means to achieving the objective of “health for all people of all nations.”

Because one of his connecting flights was delayed and a rebooking had to be done, he arrived in Almaty without his luggage. Since there was no time to buy a suit, he delivered his speech in his slacks and sweatshirt.

Federation

It was also in 1998 when the MMG chapters banded into the MGHHSCP Federation. While it initially attracted at least 50 chapter members, many fell by the wayside. Today, according to its website, it has 19 chapter members across Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao, 17 of them classified as Members In Good Standing (MIGS) or those who have met the 5Ps requirement: submission of Papers, Presence in monthly meetings, Patronage of Federation products, Participation in activities, and Payment of the Cooperative Education and Training Fund to the Federation.

The Federation has been buying medicines and medical supplies in bulk, thus lowering the cost of health care in the MMG hospitals nationwide.

In 2019, the Federation linked up with the Department of Agrarian Reform to directly source from agrarian reform beneficiaries (ARBs) the food products their hospitals nationwide need such as rice, vegetables and root crops.

The Federation has also recently embarked on a project that would reduce the cost of electricity in their hospitals. Lower overhead cost would then translate into further lowering the cost of health care.

Unlike other CEOs, Tiongco hated formalities. In his e-mails to the Federation, he would address them as “Dir Pipol” and end his post informally, signing off as “tingalingdingdong” or “tingalingdongding” or “tingks” and its variations.

“How to multiply my heart”

With age, Tiongco minimized his beer drinking but continued to play the piano and dream of other ways to make sure the Federation fulfills its mission and vision and lives up to its philosophy.

According to the Federation’s website, its mission is “to provide adequate health care for all Filipinos through preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative services throughout the land,” its vision is “sustainable development of marginalized communities to achieve economic freedom through health in 2024” and its philosophy is “Health is a basic human right and as such, it should be universally accessible to everybody not only for those who can afford it.”

The vow of the “crazy dreamers” four decades ago has become the Federation’s motto: “Until every pain and affliction, every cry of anguish and hunger can seek attention and care, without fear of inaccessibility, rejection nor discrimination … Until then, our work is never done!”

And the work will continue even without Tiongco’s physical presence because he had multiplied not only his mind and hands, but also his heart.

When he trained young doctors to become surgeons, he did so to “multiply my mind and my hands” but did not yet know “how to multiply my heart.”

The health cooperative movement taught him how. And he showed them how in the 32 years he served as leader.

Tiongco is survived by his daughter Amane, siblings Nora Ermac, Erna and Pepe Gatmaitan, Gladys San Juan-Tiongco, Alex Tiongco, Rita and Oscar Paras, Joy and Guido Delgado, nephews and nieces and in-laws, and their children.

In lieu of flowers, the family “would appreciate donations” to the Medical Mission Group Hospitals and Health Services Cooperative of the Philippines Federation, Metrobank Account Number 199-7-199-53010-7. (Carolyn O. Arguillas / MindaNews)

Source: https://www.mindanews.com/top-stories/2023/05/dr-ting-tiongco-father-of-health-cooperatives-passes-away/