Mariamme D. Jadloc – Diliman Information Office

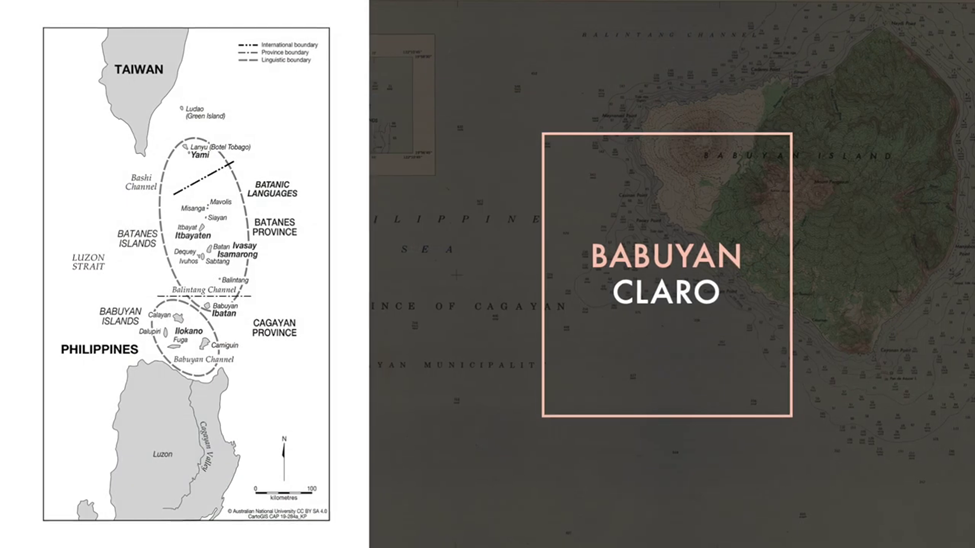

In the northernmost island of Luzon lies the community of Babuyan Claro.

It is home to the Ibatans.

In her dissertation, The Stratigraphy of a Community: 150 Years of Language Contact and Change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines,Maria Kristina Gallego, PhD said the Ibatans “… emerged from a century and a half of intense social contact between people from different, but closely related, ethnolinguistic groups: Ivatan and Itbayaten (Batanic) and Ilokano (Cordillera).”

Gallego is an assistant professor of linguistics and chair of the UP Diliman (UPD) Department of Linguistics (DLingg) of the UPD College of Social Sciences and Philosophy.

Northern tip. Babuyan Claro belongs to the Babuyan group of islands at the northernmost islands of the Philippines, under the township of Calayan. It is a small island with a rugged terrain and generally lacks exploitable natural resources.

Gallego said, “Until several decades ago, this region was relatively isolated from the rest of the country given the extreme difficulty in crossing the Babuyan and the Balintang Channels.”

First families. Babuyan Claro traces its beginnings from one family’s attempt to return to their homeland. But they ended up establishing a new home for themselves.

According to Gallego, there was a group composed of five persons from Calayan and Camiguin that were shipwrecked on Babuyan Claro in their attempt to go back to Batanes. These were Alvaro and Maria, both of Batanic ancestry, and their Ilokano friends Fidel, Mauricio, and Marcelino.

“For the next 50 years or so, Babuyan Claro witnessed similar arrivals of small groups of people from Batanic- and Ilokano-speaking groups,” Gallego said.

Language. Ilokano is used as the lingua franca in Babuyan Claro, but the local language of Babuyan Claro is Ibatan and it is used by about 3,000 first- and second-language speakers.

“It belongs, linguistically, to the Batanic sub-group along with the languages of Batanes, Ivatan, and Itbayaten and also Yami or Tao which is spoken in Orchid Island in Taiwan,” Gallego said.

Distinct lines. The present-day Babuyan Claro community is an outcome of the coming together of families from either Batanic or Ilokano-speaking ancestry.

The general preference in keeping ethnolinguistic lines separate during the early years of Babuyan Claro is reflected in how residential settlements have developed on the island.

“While settlements are scattered in the whole island, the greatest density is found on the southern slopes of Chinteb a Wasay (Mount Pangasun), which is a very active volcano. This concentration of settlements forms the basis of the geographic region laod or west and daya or east, where laod refers to the sitios or hamlets of Kadinakan, Idi, Barit, and Kasakay. Whereas daya or east, while technically referring to the sitios east of laod has come to refer to all other sitios outside laod. Despite the short distance of the sitios in laod and daya, there exists an apparent social division between the two regions based primarily on the nature of these residential settlements,” Gallego explained.

Significant clusters of speakers residing in laod consists mostly of mixed Ibatan-Ilokano families. Gallego said they show greater affinity towards using Ilokano as their everyday language, whereas families from daya show greater affinity towards Ibatan.

Rise of Ilokano. “While egalitarian multilingualism resulted in the emergence of the Ibatan language and its co-existence with Ilokano during Babuyan Claro’s initial years, the integration of the community within the wider administrative region of Calayan has led to a shift in the nature of multilingualism on the island,” she explained.

In the 1970s, the center of community activities was in the laod region, the region associated with Ilokano speakers.

“The Roman Catholic church and cemetery were both in the city of Idi and most religious activities were mostly conducted in Ilokano. At that time, the dominant religion in Babuyan Claro was Roman Catholic. The teachers on Babuyan Claro were also Ilokano immigrants and so instruction was done in Ilokano and to a limited extent, Filipino. In the 1980s, the only school on the island did not go further than Grade 3. So, imagine if you want to proceed to higher learning of education, Grade 4, you need to transfer to Calayan, which is about a five-hour boat ride from Babuyan Claro,” Gallego said.

The extreme difficulty in crossing these islands prevented the mobility of the school children. They had to stay for a long time in the municipal center of Calayan. Calayan is also where the Ibatans have reported discrimination because of their ethnolinguistic identity. Ilokano is the main language spoken in Calayan.

All these have severely threatened the vitality of Ibatan.

Revitalization of Ibatan. The empowerment and more vigorous use of Ibatan began in the 1980s with the arrival of Rundell and Judith Maree of the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Gallego said the island saw the establishment of a Protestant church, a rural health unit, and the first water supply on the island in Kabaroan—the center of Ibatan-speaking families.

“According to Rundell Maree, the choice of Kabaroan as the new village center was intentional. If the Ibatan language was going to survive, we had to give the area in which the Ibatan people lived some greater prominence. In terms of literacy and education, Ibatan books, readers, and even a newspaper boosted reading proficiency,” Gallego said.

In 2004, the local school on Babuyan Claro was expanded to include high school education, and in 2016, they started to offer the additional years of senior high school. Nowadays, the students can now opt to stay in Babuyan Claro for the duration of their basic education. The students now have the option to go to the mainland only when they go to university.

On June 1, 2007, the Ibatan people were officially recognized by the Philippine government as the 111th indigenous cultural community. They were awarded their certificate of ancestral domain title that grants them exclusive rights to Babuyan Claro and Ditohos islands and its surrounding waters.

“All these changes in the ecology of Babuyan Claro have re-shaped and continue to re-shape the linguistic repertoires of the people of the island. Although generations report greater proficiency in Ilocano as their second language for example, but now some younger speakers report greater proficiency and actually preference towards using Filipino as their second language. And they are not too comfortable in using Ilocano anymore,” Gallego said.

Multilingualism. Gallego found that Babuyan Claro’s dynamic social linguistic landscape also has an influence on individual level patterns of multilingualism.

Gallego said the story of Babuyan Claro is a clear example of a fragile socio-linguistic setting, where the kind of egalitarian multilingualism that existed in the past which favored the emergence of Ibatan has changed to a more hierarchical one at present. This led to shifts in the language ecology of the community.

“So while particular sociopolitical changes have resulted in more positive attitudes and greater use of the Ibatan language, its viability in the future is not certain precisely because of the dynamic nature of the community. It is only with long-lasting social change that we can be certain of the Ibatan people’s and language’s continuity in future generations,” she said.

Gallego presented part of her dissertation in Paglulunsad at Paglalayag, a paper presentation and website launch, in November in celebration of DLingg’s centenary.

Source: https://upd.edu.ph/stories-from-babuyan-claro